Food as Healing, Connection & Preservation: Sin Maíz No Hay País…sin mujeres, no hay vida

“Without maize, there is no country… without women, there is no life.”

Collective activism to set forth social change has been an interest of mine since I was 10. It reminds me that humans can in fact unite for a common cause, while also sharing knowledge and empowering each other, usually positively impacting the most vulnerable. Sin Maíz No Hay País, which translates to, “Without Corn (Maize), There is no Country,” was a national campaign led by farmers and college students in the early 2000s in Mexico. The main focus was the conservation and protection of native seeds- Non-GMO corn. During the time this movement gathered national support, native maize in Mexico was on the brink of becoming extinct. Corn is a staple of Mexican gastronomy. Maize cultivation and domestication dates back to the Aztec empire over 10,000 years ago. It took an entire nation led by youth and farm laborers to ignite passion for the protection of a single seed of corn.

I love handmade corn tortillas; they are special to me for various reasons. My most fond memory, and also the earliest, is when I took a bite of a warm squished tortilla filled with lime drops and sprinkled with salt. Tortilla con limón y sal is every toddler’s right of passage. Don’t ask me how, but I have vivid memories as young as three years old, mostly involving food. I still remember enjoying these as a toddler.

My mom moved to New York when I was five years old. We reunited when I was seven. To make this trip possible, she began a tortilla business and bought a gigantic metal comal. In the southern part of Mexico, maíz tortillas are predominant, whereas in northern Mexico, flour tortillas are a staple. My siblings and I made trips to the molinero to pick up daily supplies of nixtamal; I only tagged along because they used to help my mom watch me. Both of my sisters hated to be seen pushing big containers of nixtamal home, so my youngest brother made the trips. Him and I bonded during these trips. My mom then grounded nixtamalized corn to make handmade tortillas and sold them by the dozen. Before piles of tortillas were bagged for the pick up/delivery orders, I always got the first tortilla, squeezed gently and blown to cool down for my little hands to be able to hold and not get burned while taking a bite. The lime and salt in the inside of the tortilla balanced the cal found in nixtamal.

In a sense, we owe our American Dream to tortillas de maíz. And I’m very proud of how humbling that is, even if my two sisters would have been caught dead before being seen by their friends from la preparatoria (HS) pushing el diablito con el nixtamal. This is still a joke in our family.

Nixtamalization is a process for the preparation of maize, in which the corn is soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution, usually limewater (calcium hydroxide), washed, and then hulled. This process enhances the flavor and nutritional value of the grain. Prior to mechanization of tortilla making, women traditionally would grind nixtamalized corn on a stone-ground tool called a métate. In many homes this is still practiced and is preferred over store bought tortillas from tortillerias, local shops which produce large amounts of tortillas using machinery.

Tortilla making has predominantly been practiced by women. My first job at a higher end restaurant in NY, during the beginning of my career in hospitality, was at Rosa Mexicano at Lincoln Center. One of the biggest highlights of the experience there were the tortilleras who were stationed facing the upper dining floor. Everyday during service, two women pressed masa and produced hundreds of corn tortillas. This was the first time I recognized the value and intricacy of tortilla making. They were the only individuals who were hired to do this job. Not everyone had that talent or technique. They were truly valuable, and their relationship with the executive chef was also unique. Because this technique is taught mostly to women, Mexican women have really taken this talent and run with it, in many instances using home cooking knowledge to support their families. According to Harvard researcher Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato, “since tortilla-making remained unmechanised, it allowed hundreds of women to establish tortilla shops that mostly hired women. Their entrepreneurship can be considered a survival strategy of women confronting a technological change in an era of political, social and economic turmoils.”*

*Female entrepreneurship as a survival strategy: women during the early mechanisation of corn tortilla production in Mexico City. Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2020

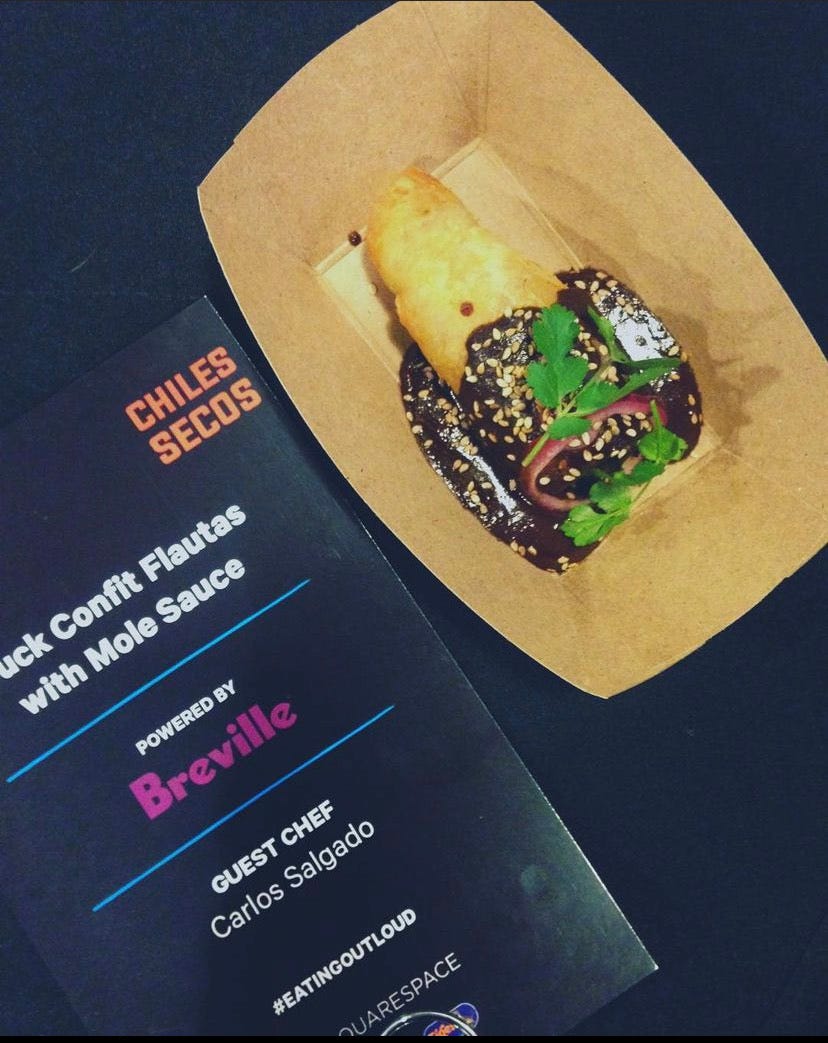

In 2015, I was hired to open one of the stalls at Grand Central Market. Historically, this place has had a big economic impact on immigrant families here in Los Angeles. Its layout is reminiscent of a Mercado in Mexico, an open spaced produce market. A piece of Mexico in Los Angeles, a place where no matter how many times it transforms itself, you can’t hide the strong relationship between Mexican and Angeleno culture in the dining scene, as well as its influence in popular culture. Thanks to social media, I met the granddaughter of the man behind one of the most influential and loved stalls at GMC- Chiles Secos. Claudia approached me to help her come up with a way to help her promote her family’s business during the time GCM was experiencing transformation and gentrification. Although its popularity brought hundreds of guests daily, it too was making some of the original stalls fight for survival. The story of Grand Central Market is very interesting to those who experienced the big change first hand. I jokingly called the marketing plan, “Taking Back Grand Central Market.” It worked because they are still standing, even after a global pandemic.

One of the marketing strategies we planned was collaboration with outside Mexican-American chefs during market events, because they understood the importance of Chiles Secos and Grand Central Market’s history. Many of them had visited the stall with their families while growing up. One of the chefs I contacted was Chef Carlos Salgado of OC’s Taco Maria. He was one of the very few highly regarded chefs working with nixtamalized organic Mexican maize, producing and making tortillas out of his small restaurant, now a Michelin starred eatery. For our first event, we picked up masa, or corn meal from BS Taqueria in DTLA, a place which also carried Chef Carlo’s organic blue and yellow masa. Someone made deconstructed tamales using Chef Carlos’ masa and Chiles Secos’ spices and they were sold. Some people who came to the stand commented negatively about the price that was charged per tamal. I explained the process of making the masa and tamales was labor intensive and pointed out that as Mexican-Americans, we should support more Latinx business and end the notion that Mexican food must be cheap in cost, when the technique and knowledge is complex. I also mentioned the importance of Carlos Salgado’s work, who was on a mission to save non-gmo corn and the efforts of the Mexican movement, Sin Maíz No Hay País. He was one of the very few chefs pushing for more awareness of this issue and urging others to partake in the conservation of this single seed. In 2015, this was a hard conversation to have and very difficult to educate others about.

Claudia and I also lead a tortilla class during a different event held by Grand Central Market. I love sharing with people the importance of food equality and conservation. My mom's entrepreneurial dreams were never for herself either. She shared her skill with others and for her family.

Two important things to take from this is that financial autonomy and food conservation and knowledge is truly the key for the advancement of our communities. I hope you think about this next time you take a bite of a warm handmade corn tortilla.

Con amor,

Yuri Maldonado

Coolio!