What's in a Name?

Oysters of Washington State

Fat Bastard, Shinnecock, Moonstone, Naked Cowboy… who thinks up these names for oysters? The majority of people would assume that oysters of different names are of different species, right? Or at least they’re different varieties or breeds, like types of apples or dogs. Yet unbeknownst to most, there are only a handful of oyster species, and even fewer that are for human consumption. There’s a few specialty species such as the Kumamoto, originating in Japan and now also grown in some parts of the Pacific Northwest, or the copper-flavored European Flat, from France and the United Kingdom. Yet the vast majority of those consumed in the United States are one of just two species, either the Eastern Oyster or the Pacific Oyster — and that’s it! These varied and sometimes sensational names either come from geographic locations or are marketing names from the grower.

Oysters take on their particular characteristics based on where and how they’re grown. Factors like water salinity, bottom substrate, and water temperature all greatly affect the appearance and flavor of the oysters. The grower’s choices and handling have a substantial effect too, like whether the oysters are grown in “suitcases” just off the bottom of the beach or in floating bags, and whether the oysters are tumbled. [Tumbling is when the oysters are deliberately rolled, breaking off the fragile tips and causing the oysters to grow down instead of out, forming deeper cups.] Oysters grown just miles from each other using the same method can taste completely different; oysters grown in the same place using different techniques can differ greatly too. Those in the shucking business call this merroir. Like terroir in wine, pinot noir grown in the Willamette Valley will taste very different from the same grape grown in the Santa Rita Hills… or Burgundy for that matter. The importance of place in the taste is pronounced with oysters because they are filter feeders, they are what they eat. Two Pacific oysters, the same species, grown just miles from one another, with one living in the mud near a river mouth and the other in floating bags at the open ocean, will have distinct flavors. Commercial oysters are, therefore, one of the few living things for which the question of “nature vs. nurture” actually has a clear answer. The individual differences in oysters that go by different names is accounted for considerably more by nurture, environmental and human, than their intrinsic nature.

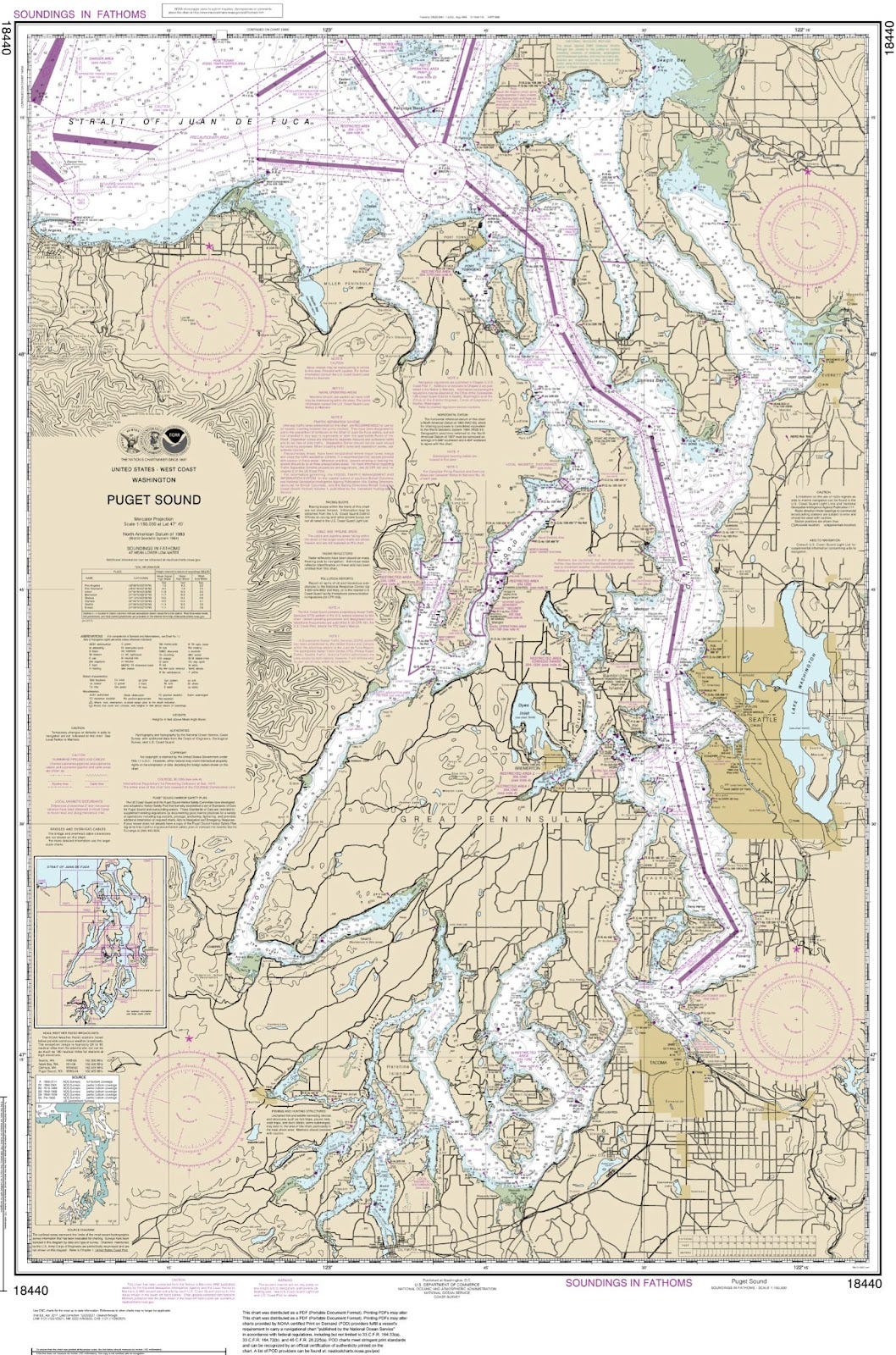

One of the finest illustrations of this phenomenon is found in the Salish Sea, the top corner of the Pacific Northwest. If the Puget Sound is like an arm curling into Washington state, with the inlets at the bottom like fingers on its hand, the Hood Canal across from it is like a fishing gaff. Though the Puget Sound is more craggy and meandering, the two don’t appear to be altogether that different, at least on a map. Yet they differ greatly and the oysters that grow there, even though they are mostly the same species, are distinct in appearance and flavor. Together, they produce some of the country’s finest oysters and in great quantity. To understand why, we must jump through time, looking back millions of years. In the area around what is now Seattle, the collision and fusion of land masses pushed up the Olympic and Cascade mountains, the land was groomed over thousands of years by massive glaciers sliding out to sea. The Hood Canal was carved by such movements, with the steep Olympic Mountains to the West, and the deep gravel bottom below. The Puget Sound lowlands were created by glaciers too, but were influenced at least as much from their movement as their melting, with the subsequent flooding and draining that ensued. This formed the many inlets around the sound, leaving behind the clay, sand, and mud along the bottom and shores. The differences in nature between these two bodies of water account for so much of the differences in the oysters produced here.

The legacy of Washington State’s geographic history lives on in its oysters. With its deep mineral-laden water and rocky bottom, the oysters from the Hood Canal generally taste like cucumber, and subtly perhaps lemon zest. The Hood Canal is not as long as the Sound, so the influence of the Pacific ocean is stronger, and they tend to have a medium to strong salinity brine. One of the best examples is the Hama Hama’s namesake oyster, from the middle of the Hood Canal. Though their oysters are found on menus around the country, Hama Hama is a 5th generation family-owned oyster farm. One of their partner farms, the Hansen & Kadoun families, grows an oyster they call Sea Nymph, from the south part of the Puget Sound in the Hammersley Inlet, which are a prime example of the Sound’s contrasting flavor. They’re less briny, as the south Sound is much further from the Pacific, and though they still present some of the green melon rind flavor that’s present in nearly all Pacific oysters, they taste more of earth and kelp from the algae-rich water. Next time you see two oysters on a menu that are from the same state, especially Washington, give them both a try. Chances are you’ll be surprised by the contrast.