WTF is Burrata?

Some kind of food alchemy, it must be.

What is burrata anyway? And why do we love it so? Some kind of food alchemy, it must be, as it’s so much better than milk. Because it’s essentially fresh mozzarella mixed back in with cream, then wrapped in a delightful little pillow of mozzarella to keep it from oozing apart. “Mozzarella with a heart of cream,” to borrow LA Times food critic Irene Virbila’s words from two decades ago, when she wrote about its then introduction to Los Angeles (more on that later). That sneaky cream, disguised in a coat of cheese, is the magic maker.

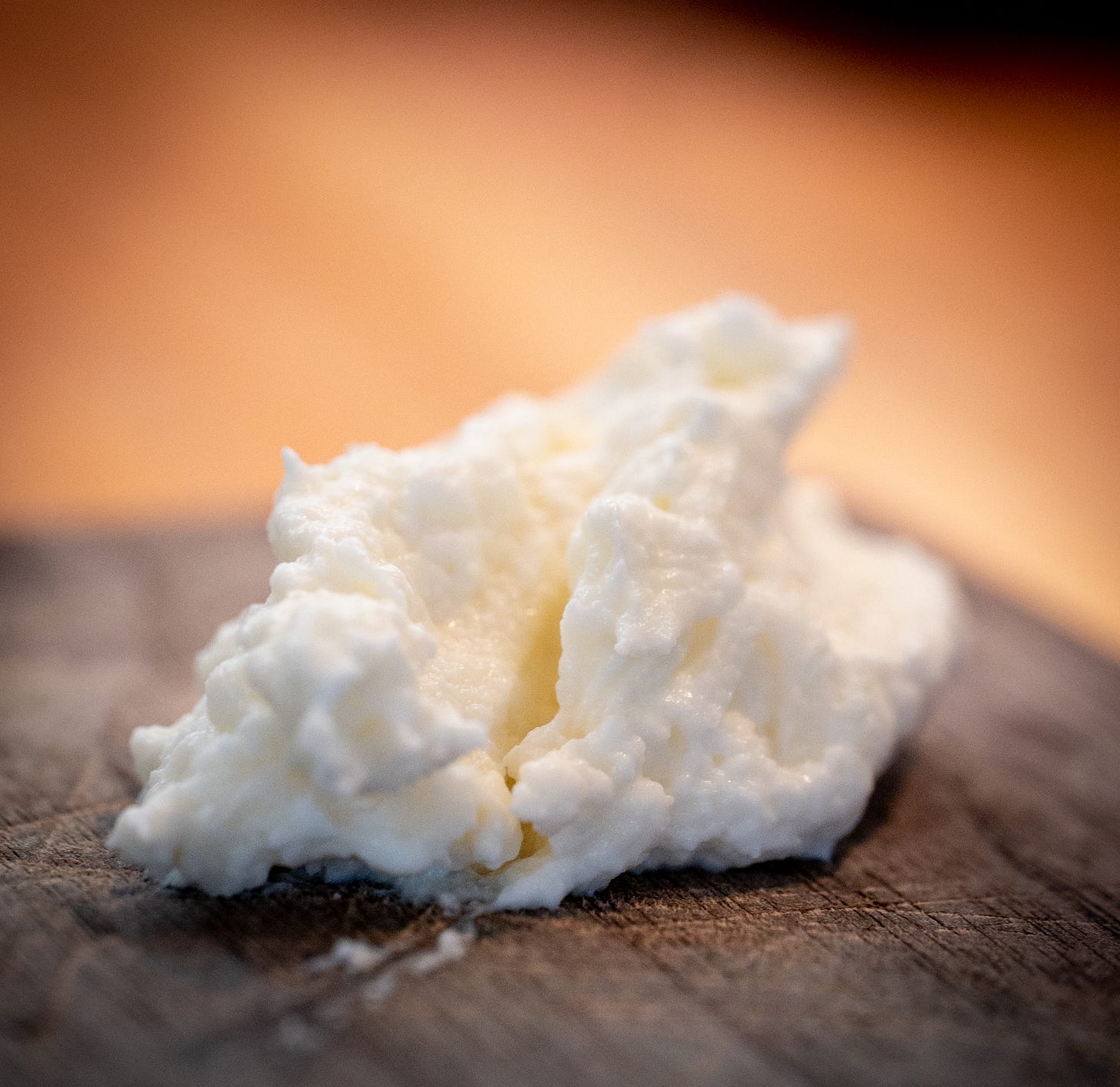

It starts with milk, of course, which is brought in fresh from California, still raw (unpasteurized). Most small producers here pasteurize it themselves, so they can control the process carefully and heat the milk minimally, preserving its flavor. Rennet and cultures are added to the milk, causing the casein proteins to clump together into curds, and leaving whey proteins floating in the liquid. The curds are separated and go into hot, usually lightly salted water, and the stretching begins. This process makes the curds moist and elastic. They are pulled into ropes and draped over a bar like pasta drying or wool being dyed. From here the stretched curds can go in several directions. If you form it into a ball or a braid or a knot, and put it into a container with some of that water — it’s done. It will be mozzarella. But if it’s pulled horizontally into smaller strands, and mixed into a giant bowl of cream, it becomes stracciatella — little rags, stretched strands. And this is wonderful stuff. But now take another piece of the mozzarella, coax it out flat like dough, and use it to scoop up some of the stracciatella, then twist & wrap that pouch onto itself. And there you have it: burrata.

Brought to us from Puglia, burrata is traditionally made in Italy with buffalo milk. The buffalo is a cousin of our domesticated cow, which is what we primarily use here in the US of A for burrata and mozzarella. Buffalo milk has higher everything — more fat, protein, lactose, vitamins & minerals — as compared to cow’s milk. In fact, buffalo milk has almost double the fat content. It’s whiter and thicker in consistency because of all those extra suspended fats and proteins, producing a bright white cheese with a grassier, “cowier” flavor. You may be suspicious of it because it is less familiar to you, but from an objective standpoint on the subjective matter of taste, it is simply better. Though you might not like “di bufala” right now, perhaps your palate will get there one day. Anyhow, with a lack of buffalo around and plenty of cows, and moreover an American palate accustomed to cow’s milk, by-and-large we make it with cow’s milk here.

As the story goes, Mimmo Bruno of DiStefano Cheese brought burrata (and other cheeses) around to Los Angeles to see if some restaurants would be interested in becoming his customers. After some rejection from chefs in town about his “new” cheese, he met with Chef Nancy Silverton, who had just returned from a trip to Italy, and was not only familiar with burrata but fond of it. She put it on the menu at the beloved Campanile, in a sandwich. The LA Times featured it in the 1998 review quoted above, and the rest is history. But burrata, because it’s so easy to enjoy even on its own, must be utilized with a measure of care. Otherwise, now that burrata is immensely popular, it risks becoming trite. Unless it is made in-house, or imported burrata di bufala, or something else worthy of being enjoyed unadorned even at a restaurant, the lazy impulse to put burrata on plate with little more than flaky finishing salt and a drizzle of viscous balsamic, or to put burrata in several places on the menu to give otherwise lackluster items greater appeal, must be controlled. If we, as chefs and eaters, don’t manage that urge, burrata will be like a song you loved but was overplayed until you couldn’t stand it anymore. The noted exception aside for special burratas, look for thoughtful combinations where burrata creates balance or synergy with other ingredients. But I digress, and should step off my soapbox to continue our story.

For burrata and stracciatella, the Gjelina Group uses Gioia, a 4th generation cheesemaker in Los Angeles who delivers the cheese in the morning. The 3rd generation cheesemaker, Vito, came over from Italy in 1992 with his family and opened Gioia Cheese. Timing is everything, as they say. 30 years later at Gioia the burrata is still formed by hand, in this case by two women with deft and burly forearms working side by side over a huge bowl of stracciatella. Executive Chef Juan Hernandez and I went to Gioia back in 2018, when we were being courted by another local cheesemaker (there are several in LA now) to change over our burrata, ricotta, and mozzarella business. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to take photos from within either producer’s facility, as we were sanitized from shoes to beard nets, so camera phones remained off the production floor. After visiting both producers, we decided to stick with Gioia because it is still traditionally made and moreover has unsurpassed flavor. With no preservatives, low salt, and high moisture content, burrata’s shelf life is short. Yet its uses are many and its legacy is long.

seems like it has been around forever. Nice article.

As an Italian American I thoroughly enjoyed reading this piece :) And even found out some great info! Nancy Silverton’s the best — bless her soul for bringing burrata into the food scene here. Places like Gjelina make my heart sing 🧡